Then Naomi her mother-in-law said to her, “My daughter, shall I not seek security for you, that it may be well with you? Now Boaz, whose young women you were with, is he not our relative? In fact, he is winnowing barley tonight at the threshing floor. Therefore wash yourself and anoint yourself, put on your best garment and go down to the threshing floor; but do not make yourself known to the man until he has finished eating and drinking. Then it shall be, when he lies down, that you shall notice the place where he lies; and you shall go in, uncover his feet, and lie down; and he will tell you what you should do.” (Ruth 3:1-4)

Naomi knew it was just a matter of time. Once the harvest was over, their livelihood would again be in jeopardy unless…unless a kinsman redeemer[1] would step in and come to their rescue. Boaz, though not the nearest relative, would be their first resort. After all, he already knew Ruth and had shown a concern for her welfare as well as, by extension, Naomi’s own. The time had come for a bold plan.

At the threshing floor

English: Threshing place. The circle is made from concrete. Harvested straw is put on the concrete surface and a donkey is made to walk on it in circles, which causes the process of threshing. On the left (front of the picture) visible leftovers (mostly tailings and chaff). Around the perimeter there is some threshed straw. On the floor there are some threshed grains. Photo taken near Vlyhada (Santorini, Greece). (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Boaz worked alongside his hired men at the threshing floor—a cleared solid surface of hard-packed dirt or rock—preparing for the final stage of the weeks-long harvest.[2] Ruth watched as this kind kinsman, or was it one of his workers, expertly urged draft animals, whether oxen or donkeys is unclear, to drag heavy threshing sledges[3] back and forth over the sheaves, breaking down the stalks into husks, straw, and grain kernels. Then experienced hands wielding wooden pitchforks lifted the straw away so the process of winnowing could begin.

Winnowing the Chaff | Bamiyan (Photo credit: Hadi Zaher)

In the cooling evening breezes, waiting crews used winnowing forks, tossing the remaining grain into the air. Mesmerized, Ruth watched lighter stalks and husks (the chaff) be whisked away on capricious currents of wind, and the heavier kernels plummet back to the floor in a haphazard heap. Then mounds of the tawny pellets were scooped up and sifted through trays to remove any remaining dirt and debris. The clean grain was finally ready for immediate use or storage in sealed clay jars.

As the last rays of sunlight grew dusky, weary workers allowed themselves to relax, enjoying food and drink, celebrating harvest’s end. Bellies full and hearts merry, first one and then another fell silent, except for an occasional grunt and snore. Ruth’s gaze followed Boaz through the dimness as he made his way to the end of a grain pile, spread his blanket, and quickly dropped off to sleep.

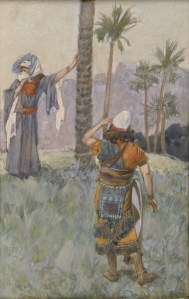

Naomi’s instructions had been quite clear: Wash yourself, put on your best garment, go back to the threshing floor, and wait for the moment of opportunity. That time had come. Ruth quietly made her way to where Boaz lay, uncovered his feet, and lay down.

The Kinsman-Redeemer

Naomi’s strategy was one of enlisting the involvement of the kinsman-redeemer.[4] Now Ruth lay at Boaz’s feet, anticipating the opportunity to bring Naomi’s plan to fruition. His sleep suddenly troubled, she watched him awake with a start sensing her presence in the darkness. “Who are you?” he challenged warily. Ruth responded with her request. “I am you servant Ruth,” she said. “Spread the corner of your garment over me,[5] since you are a kinsman-redeemer” (3:9 NIV).

Flattered by Ruth’s request, Boaz commended her for approaching him, since it is likely that he was considerably older than she, and she might well have chosen a younger man. Rather than interpreting her actions as wily and improper, he afforded her only kindness and respect.[6] He encouraged her to wait until morning for the sake of her reputation and for her own protection. Before first light she could safely return to Naomi, and none would be the wiser. Then he would attend to the business at hand.

Following the rules

Boaz knew there was a kinsman closer than he, and his integrity dictated that he go to him first before proceeding any further. By rights, this relative (who, though unnamed in the Bible, was obviously known to Boaz) could redeem Elimelech’s land either by buying it back, if it had indeed already been sold, or he could buy it outright.

Now Boaz went up to the gate and sat down there; and behold, the close relative of whom Boaz had spoken came by. So Boaz said, “Come aside, friend,[7] sit down here.” So he came aside and sat down. And he took ten men of the elders of the city, and said, “Sit down here.” So they sat down. Then he said to the close relative, “Naomi, who has come back from the country of Moab, sold the piece of land which belonged to our brother Elimelech. And I thought to inform you, saying, Buy it back in the presence of the inhabitants and the elders of my people. If you will redeem it, redeem it; but if you will not redeem it, then tell me, that I may know; for there is no one but you to redeem it, and I am next after you.'”

And he said, “I will redeem it.”

What happened next affords a certain opportunity for speculation. Was Boaz disappointed when the near kinsman quickly accepted the responsibility? He obviously had more than a casual interest in Ruth and her welfare. Or had he anticipated just such a response, and, as the astute business man he undoubtedly was (Scripture describes him as a mighty man of wealth), knew just when to bring up an additional requirement to put the negotiations in jeopardy? Note the various translations of verse 5 below:

Then Boaz said, “On the day you buy the field from the hand of Naomi, you must also buy it from Ruth the Moabitess, the wife of the dead, to perpetuate the name of the dead through his inheritance” (NKJV).

Then Boaz said, “On the day you buy the land from Naomi and from Ruth the Moabitess, you acquire the dead man’s widow, in order to maintain the name of the dead with his property” (NIV).

Then Boaz said, “The day you acquire the field from the hand of Naomi, you are also acquiring Ruth the Moabite, the widow of the dead man, to maintain the dead man’s name on his inheritance” (NRSV).

Boaz had just introduced the obligation of a levirate marriage, and the kinsman, recognizing the inherent liabilities that such an arrangement could impose on his own family, quickly forfeited his right of redemption to Boaz.[8] So, in the presence of ten official witnesses and many onlookers, Mr. So and So removed his sandal, thereby signaling the transfer of the property. A communal blessing followed:

And all the people who were at the gate, and the elders, said, “We are witnesses. The LORD make the woman who is coming to your house like Rachel and Leah, the two who built the house of Israel; and may you prosper in Ephrathah and be famous in Bethlehem. May your house be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah, because of the offspring which the LORD will give you from this young woman” (vv. 11-12).

The rest of the story of Ruth

So Boaz took Ruth and she became his wife; and when he went in to her, the LORD gave her conception, and she bore a son. Then the women said to Naomi, “Blessed be the LORD, who has not left you this day without a close relative; and may his name be famous in Israel! And may he be to you a restorer of life and a nourisher of your old age; for your daughter-in-law, who loves you, who is better to you than seven sons, has borne him.” Then Naomi took the child and laid him on her bosom, and became a nurse to him. Also the neighbor women gave him a name, saying, “There is a son born to Naomi.” And they called his name Obed. He is the father of Jesse, the father of David” (vv. 13-17).

Ruth, Naomi and Obed. Pen and brown ink over pencil on paper. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Summary

The book of Ruth, in its four short chapters, gives one of the few detailed glimpses into the everyday lives of Old Testament characters in the Bible, and in particular, women. The reader is exposed to the nuances of the desperate plight of three widows, two of whom found themselves displaced and in foreign lands; and marvels at their courageous efforts to survive by hard work and ingenuity. The reader senses the depth of the bond of devotion to both kin and God, and the bitter anguish of loss. The reader observes the realities and rigors of harvest and manual labor; and sits as one of the collective witnesses to the legal proceedings involving rights of inheritance and preservation of a family line. Lastly, the perceptive reader will recognize and value this book as a beautiful exemplar of kindness, the evidence of which is found on every page.

What a gift to have The Book of Ruth preserved in the pages of the Bible!

***

For additional reading please view Mary Hendren’s post, Levirate Law– in Confusion.

The Writings

***

[1] A Ga’al (Strong’s 1350), or kinsman redeemer, could act in several ways. By definition according to http://www.biblestudytools.com/lexicons/hebrew/nas/gaal.html , the kinsman redeemer could marry a brother’s widow to beget a child for him (Deuteronomy 25:5-10), redeem from slavery (Leviticus 25:47-49), redeem land (Leviticus 25:25), or exact vengeance (Numbers 35:19). In the book of Ruth, Boaz acted as a levir as well as one who preserved claim to the family property.

[2] It is possible that Boaz, and /or others, were overseeing the process. The Archaeological Study Bible, in its cultural and historical note on “The Threshing Floor” (page 608), comments that because the threshing floor was the largest open area within a village,“town elders were typically present to oversee the threshing of the year’s crops.” The threshing floor was also a suitable locale for “legal actions, criminal trials, and public decisions.” The city gate was also used for such proceedings as will later be seen.

[3] Sledges were heavy wooden slabs with teeth made of stone, metal or potsherds fastened to the underside. See Isaiah’s vivid description of the whole process in chapter 41, verses 14-16.

[4] Whether this was simply to assure that Elimelech’s landholdings would be preserved within family lines, or to ensure there would be a son to carry on the family name, or both, are topics for on-going discussion. Leon Wood, in his book, The Distressing Days of the Judges (1982), addresses both: “When an owner was forced to sell property due to poverty, it was the obligation of the nearest relative to buy this property back (thus ‘redeeming’ it), so that it could remain in the possession of the original family” (p. 261). Wood goes on to comment that “it was the obligation of the nearest kinsman, in this instance, not only to purchase the property of Naomi—which really also belonged to Ruth, because of inheritance rights through her dead husband Mahlon—but also to marry Ruth and raise up a son to Mahlon who might then inherit that property in due time” (p. 262).

[5] Scholars do not agree as to the meaning and symbolism associated with this action. Some feel it amounted to a request for protection, while others interpret it as a request for marriage. For a detailed examination of challenges present in the wording of the Hebrew text see

http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/otesources/08-ruth/texts/books/leggett-goelruth/leggett-goelruth.pdf, pp. 192-3.

[6] Some have chosen to attribute to both Ruth and Boaz activities or motives of a sexual nature, but others, such as The Expositor’s Bible Commentary in its note regarding Ruth 3:13, write to the contrary: “Both Ruth and Boaz acted virtuously in a situation they knew could have turned out otherwise. Chastity was not an unknown virtue in the ancient world.”

[7] The word friend (NKJV) and kinsman (KJV) in this verse is taken from a Hebrew idiom best translated “Mr. So and So.” It is translated as such in the Tanakh. This idiom is said to have been used when it was not deemed essential to use the person’s actual name. Some think they detect a certain disdain attached to its usage here, since the relative declined to step in to help. See The Expositor’s Bible Commentary comments on Ruth 4:1-3.

[8] Expositors comments concerning 4:6:”Most scholars interpret the kinsman’s refusal as an awareness that he would be paying part of what should be his own children’s inheritance to buy land that would revert to Ruth’s son as a legal heir of Elimelech.” Others posit he was reluctant to intermarry with a Moabite woman (cf. Deuteronomy 23:3-4).

Keil and Delitzsch Commentary on the Old Testament comments on verse 6: “The redemption would cost money, since the yearly produce of the field would have to be paid for up to the year of jubilee. Now, if he acquired the field by redemption as his own permanent property, he would have increased by so much his own possessions in land. But if he should marry Ruth, the field so redeemed would belong to the son whom he would beget through her, and he would therefore have parted with the money that he had paid for the redemption merely for the son of Ruth, so that he would have withdrawn a certain amount of capital from his own possession, and to that extent have detracted from its worth. ‘Redeem thou for thyself my redemption,’ i.e., the field which I have the first right to redeem.”(Keil and Delitzsch Commentary on the Old Testament: New Updated Edition, Electronic Database. Copyright © 1996 by Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved.)